William Astor

The Astors

The roots of modern day astor go back to the year 1874 when William B. Astor Jr managed to buy 12,000 acres of land along the St Johns River, the name of the town was called Manhattan. William Astor was a decedent from a very wealthy John Jacob Astor, American first multi-millionaire. Early settlers of Manhattan built a church, school, botanical garden and a cemetery.

William Astor died in the spring before the worst freezes Florida has ever seen. His property was then inherited by his son John Jacob Astor, who went died with the Titanic in 1912. John Jacobs heir was William Vincent Astor who sold his interest to a Duluth Michigan Land Company in 916.

One of Astors most colorful characters was tough Barney Dillard Sr, who came to Florida in 1868 and settled in the area, rising 15 children.

Dillards son became one of the principal citus growers and shippers in Florida. Rumor has it Barney is still remembered for his rufusal to let construction crews build the Astor Bridge in 1926 which touched an ancient tree known as the Dillard Oak.

Dillard is the source of information that it was under that particular tree in 1818 that the Seminole Indians signed a peace treaty giving up all claims to anything in the Astor area.

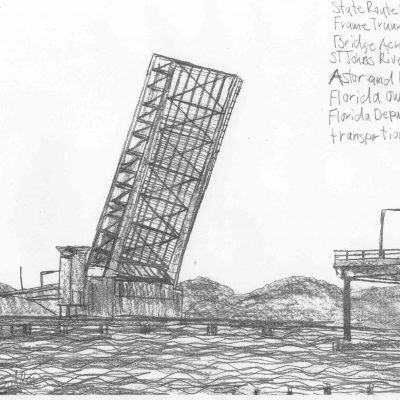

Pencil sketch of the Astor Bridge

Harriet Beecher Stowe

In the years following the Civil War, famed author and abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe painted a number of canvases of Florida oranges. One in particular resembles the view from Stowe’s window, displaying a cluster of fruit cascading down a leafy tree. Stowe completed this painting after 1867, when she purchased an orange grove in Mandarin, Florida—a move southward that might have seemed a curious decision for an ardent abolitionist. But purchasing southern land and transforming former plantations into smaller cotton farms and orange groves was considered at the time a charitable act to revitalize the devastated region and transform its political climate. Florida, in particular, was in need of revitalization; the state was dismissed as a primitive swamp and cultural wasteland made worse by the Civil War. Many northerners, Stowe included, believed an orange industry would inspire a

Harriet-Beecher-Stowe-engraving-Alonzo-Chappel-oil-1872

cultural awakening in Florida and foster a more egalitarian atmosphere that would supplant industries tarnished by slave systems.

Few scholars have investigated Stowe’s overlooked painting practice because it has naturally been eclipsed by her more prominent career as a novelist and abolitionist. Stowe published the celebrated anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852. It became the bestselling novel of the nineteenth century (and the second bestselling book of the century, behind only the Bible) and brought her world-renown as an author and ambassador for the American abolitionist movement. The novel was published in a contentious moment when debates about slavery were intensifying, and it is credited with helping to fuel both the abolitionist movement and the later push to Civil War. At war’s end, Stowe joined several northerners who migrated southward and praised her peers for “applying the habits . . . and industries of New England to . . . the Floridian soil.”

Today’s Vacationer

Mermaids in Alexander Springs

Grasshopper Lodge Ocala National Forest

Kayaking Silver Springs

Cursing down the Ocklawaha River